What is Web Scraping? As the name suggests, this is a technique used for extracting data from websites. It is an automated process where an application processes the HTML of a Web Page to extract. With that caution stated, here are some great Python tools for crawling and scraping the web, and parsing out the data you need. Let's kick things off with pyspider, a web-crawler with a web-based user interface that makes it easy to keep track of multiple crawls. It's an extensible option, with multiple backend databases and message.

This is the third edition of this post. It was originally an intro to web scraping with Python (in Python 2) using the Requests library. It was then updated to cover some extra topics and also update for Python 3.

The scenario is to download the back catalogue of the excellent MagPi magazine which is published monthly and the PDF is available for free. More info on the background is in the original post.

However, since the original post a fair bit has changed: the MagPi website was updated so the scraping broke, Python has moved on and I found that despite downloading the issues, having them on a Pi meant I never actually read them because I forgot they were there!

So this edition includes updates for all that: it works with the new MagPi website, there are more design / coding thoughts – and additional functionality such as (only) checking for new issues and then uploading to Dropbox.

Let’s get started!

Structure

The basic structure of the code is the same, but what we’d like to do in this version is:

- Start up

- Retrieve the issue number that we most recently downloaded

- Check the MagPi website to see if there is a newer version

- Additionally, handle paging

- If not, do nothing

- If yes, download the file locally

- Upload the file to Dropbox

As before, this is not supposed to be extensive or complete – it could do with more error checking and so on. A link to a repo is at the bottom.

Also as before, the code was written in Python 3.7.3 running on macOS but we’d like it to run autonomously under Raspbian on a Raspberry Pi Model 3 which only has Python 3.5.3.

We do this by editing the file in macOS and then SFTP-ing it to the Pi. FWIW, I’ve moved from Jetbrains PyCharm to using VS Code for editing. In fact, I’ve moved to VS Code for most things.

Some config

The differences in Python versions between the environments causes some issues. The obvious thing to do would be to update the Pi to have e.g., Python 3.6. However, I’ve left it as is for two reasons:

1) the Pi I’m using does other things and I don’t want to deal with accidentally borking them by updating it;

2) having this dev/prod-esque environment is quasi-real life since it forces me to do a couple of other things which will be useful.

One such example here is config. The script requires paths-to-things which are environment specific and using absolute paths helps. If these paths were hard-coded in to the script, then they’ll work locally but every time they’re transferred to the Pi they’ll break, and/or you’ll need to change them. This gets tiresome quickly so what we really want is a single script that knows how to use different paths – without having to modify the script every time – so we need to use config.

By far the simplest way to do this is in Python is to create a new config.py file, add the variables to that and then import it in the main script. You only need to now update your main script (and possibly the config if/when you add new variables.)

To use it:

So this is super easy.

Note: I’m using general coding principles that variables in the config.py are essentially public properties hence they get Capital Case. Local variables (within the script) would be camelCase.

You could obviously do this other ways, such as a .json file as config, and this would work fine. However, I rather like the autocomplete I get from VS Code doing it this way.

Side-note: another good example of why you should do this would be in the case where you have credentials / client secrets etc. You should *never* put these in public source control. So, by externalising them from your main script you can efficiently tell your source control client to ignore them without breaking everything.

Logging

It’s probably about time we did some proper logging as opposed to just writing things out to the screen. Fortunately, this is ridiculously easy in Python, using the built-in logger and some config:

This is the absolute basics. Read the docs to learn more.

Efficient scrapeage

What else. Well, now we’ve sorted some config, the other thing we need to do is store (persist) the latest issue we downloaded, and then refer to this as part of the next run of the script (rather than laboriously checking everything every time.)

There are plenty of ways to do this but in the spirit of keeping things really (really) simple, we’ll just store the latest issue in a file called latest.txt, (which is just a file with a number in it, e.g. 1)

You’ll notice the ‘WriteLatest’ method has a little check in there to only write the value if it’s higher. This is not strictly necessary and is only in there to make the initial scrape of the back catalogue simpler.

Paging

The original version of the MagPi website had all issues on one big page but now it’s paged. So we need to handle that. There are plenty of ways to do this but the simplest is to load the home page, looking for a specific div by class. It has the text ‘x of y’ pages in it; so we’ll just extract the y value:

This uses new BeautifulSoup functionality introduced in BS4 to use the ‘class_’ selector; if you’re using an older version, you may need to adjust this to use a different way to select a div by class.

Err

First potential problem if you’re entirely new to this. Hopefully you’ve followed the original post to get your Python environment setup, but if not, you may encounter an issue:

bs4.FeatureNotFound: Couldn't find a tree builder with the features you requested: lxml. Do you need to install a parser library?

This can usually be resolved using pip:

However, if the issue persists, you may also be in need of the python-lxml package:

Using sudo if you so need. This should make this particular issue go away.

Stringy

Now that we know the number of pages, we can update our search method to iterate through them:

Now we encounter our first language difference to do with string handling / formatting. Python 3.6 introduces the wonderful f-string functionality which is very similar to C#’s string interpolation:

If we don’t have this, then we need to use the older .format method:

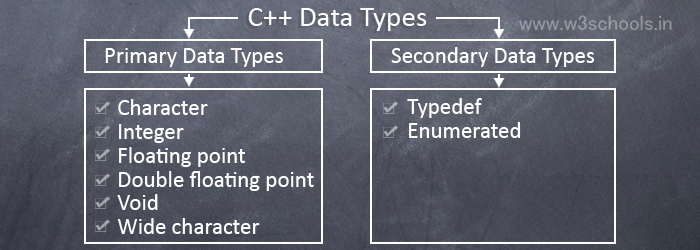

Still, this is better than the old %s replace stuff which gives me a few C++ nightmares.

For ease, I’m only using the latter method, but if you have 3.6+ then definitely replace with f-strings.

Dropbox

Moving on. As before, we hunt the issue page look for anchor tags. If we find one that matches the format we expect, we now extract the issue from it and – if that’s greater than our last retrieved – then we go ahead with downloading the PDF.

In the new version of the site, the download link is actually stored somewhere else so we go off and find it using similar methods as before.

We download the file locally, and then for extra – upload it to Dropbox.

I’m not going to go through the full setup because I just followed this which uses the open source Dropbox-Uploader shell script. The only difference is that I created an ‘App Folder’ app as opposed to Full Dropbox. Least concerns and all that.

This then just magically appeared in my Dropbox folder on my machine, which was nice.

I call the dropbox_uploader.sh script from Python using:

And that is everything. Should be ready to rock.

Done

Bear in mind that the first time it runs, it will try and download *everything* so if you want to test a bit, then update the latest.txt file to have e.g., 90 in it.

All that’s left to do is to add it to a scheduler of some sort (maybe cron…?)

With previous editions, people have struggled with the files and indentation and so on, so instead I have created a public repo (which, ftr, is my first ever public repo, ftw. Woo.) Should make snagging bugs a bit easier in the future.

As ever please comment with issues / bugs / stupid things below. There are many ways this could be done better or more efficiently but I’ve tried to keep it as simple and easy to follow as possible.

In the meantime, happy scraping!

One of the awesome things about Python is how relatively simple it is to do pretty complex and impressive tasks. A great example of this is web scraping.

This is an article about web scraping with Python. In it we will look at the basics of web scraping using popular libraries such as requests and beautiful soup.

Topics covered:

- What is web scraping?

- What are

requestsandbeautiful soup? - Using CSS selectors to target data on a web-page

- Getting product data from a demo book site

- Storing scraped data in CSV and JSON formats

What is Web Scraping?

Some websites can contain a large amount of valuable data. Web scraping means extracting data from websites, usually in an automated fashion using a bot or web crawler. The kinds or data available are as wide ranging as the internet itself. Common tasks include

- scraping stock prices to inform investment decisions

- automatically downloading files hosted on websites

- scraping data about company contacts

- scraping data from a store locator to create a list of business locations

- scraping product data from sites like Amazon or eBay

- scraping sports stats for betting

- collecting data to generate leads

- collating data available from multiple sources

Legality of Web Scraping

There has been some confusion in the past about the legality of scraping data from public websites. This has been cleared up somewhat recently (I’m writing in July 2020) by a court case where the US Court of Appeals denied LinkedIn’s requests to prevent HiQ, an analytics company, from scraping its data.

The decision was a historic moment in the data privacy and data regulation era. It showed that any data that is publicly available and not copyrighted is potentially fair game for web crawlers.

However, proceed with caution. You should always honour the terms and conditions of a site that you wish to scrape data from as well as the contents of its robots.txt file. You also need to ensure that any data you scrape is used in a legal way. For example you should consider copyright issues and data protection laws such as GDPR. Also, be aware that the high court decision could be reversed and other laws may apply. This article is not intended to prvide legal advice, so please do you own research on this topic. One place to start is Quora. There are some good and detailed questions and answers there such as at this link

One way you can avoid any potential legal snags while learning how to use Python to scrape websites for data is to use sites which either welcome or tolerate your activity. One great place to start is to scrape – a web scraping sandbox which we will use in this article.

An example of Web Scraping in Python

You will need to install two common scraping libraries to use the following code. This can be done using

pip install requests

and

pip install beautifulsoup4

in a command prompt. For details in how to install packages in Python, check out Installing Python Packages with Pip.

The requests library handles connecting to and fetching data from your target web-page, while beautifulsoup enables you to parse and extract the parts of that data you are interested in.

Let’s look at an example:

So how does the code work?

Basic Web Scraper Python

In order to be able to do web scraping with Python, you will need a basic understanding of HTML and CSS. This is so you understand the territory you are working in. You don’t need to be an expert but you do need to know how to navigate the elements on a web-page using an inspector such as chrome dev tools. If you don’t have this basic knowledge, you can go off and get it (w3schools is a great place to start), or if you are feeling brave, just try and follow along and pick up what you need as you go along.

To see what is happening in the code above, navigate to http://books.toscrape.com/. Place your cursor over a book price, right-click your mouse and select “inspect” (that’s the option on Chrome – it may be something slightly different like “inspect element” in other browsers. When you do this, a new area will appear showing you the HTML which created the page. You should take particular note of the “class” attributes of the elements you wish to target.

In our code we have

This uses the class attribute and returns a list of elements with the class product_pod.

Then, for each of these elements we have:

The first line is fairly straightforward and just selects the text of the h3 element for the current product. The next line does lots of things, and could be split into separate lines. Basically, it finds the p tag with class price_color within the div tag with class product_price, extracts the text, strips out the pound sign and finally converts to a float. This last step is not strictly necessary as we will be storing our data in text format, but I’ve included it in case you need an actual numeric data type in your own projects.

Storing Scraped Data in CSV Format

csv (comma-separated values) is a very common and useful file format for storing data. It is lightweight and does not require a database.

Add this code above the if __name__ '__main__': line

and just before the line print('### RESULTS ###'), add this:

store_as_csv(data, headings=['title', 'price'])

When you run the code now, a file will be created containing your book data in csv format. Pretty neat huh?

Storing Scraped Data in JSON Format

Another very common format for storing data is JSON (JavaScript Object Notation), which is basically a collection of lists and dictionaries (called arrays and objects in JavaScript).

Add this extra code above if __name__ ...:

and store_as_json(data) above the print('### Results ###') line.

So there you have it – you now know how to scrape data from a web-page, and it didn’t take many lines of Python code to achieve!

Web Scraping Free

Full Code Listing for Python Web Scraping Example

Here’s the full listing of our program for your convenience.

One final note. We have used requests and beautifulsoup for our scraping, and a lot of the existing code on the internet in articles and repositories uses those libraries. However, there is a newer library which performs the task of both of these put together, and has some additional functionality which you may find useful later on. This newer library is requests-HTML and is well worth looking at once you have got a basic understanding of what you are trying to achieve with web scraping. Another library which is often used for more advanced projects spanning multiple pages is scrapy, but that is a more complex beast altogether, for a later article.

Working through the contents of this article will give you a firm grounding in the basics of web scraping in Python. I hope you find it helpful

Happy computing.